Por Juan Carlos Alonso. Analista SCAJ.

Published in The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 2022, 67, 2, 412–422

Para la versión en inglés, da click aquí

Resumen: En tiempos de crisis, suelen surgir profetas en diversos ámbitos, incluido el religioso. Este artículo realiza un análisis junguiano del fenómeno observado entre el líder espiritual Osho y sus discípulos en las décadas de 1970 y 1980, como ejemplo de los riesgos inherentes a este tipo de dinámicas grupales donde líder y seguidores se identifican inadvertidamente con los arquetipos colectivos de profeta y seguidor. Se analizan las situaciones psicosociales que predisponen a la aparición de profetas y se recuerdan casos de suicidios colectivos ocurridos en las últimas décadas. El artículo también destaca la intervención de otro fenómeno psicológico: el conflicto entre la ética individual y la grupal, dado que los grupos numerosos conllevan una disminución de la responsabilidad y la ética individual.

Palabras clave: arquetipo del seguidor, arquetipo del profeta, ética colectiva, ética individual, Jung, Osho, sectas religiosas

En tiempos de crisis social, suele surgir la figura del profeta carismático y nuevos cultos, un fenómeno que se da en diversos ámbitos, no solo en el religioso. Comienza con individuos que encuentran su propio sistema explicativo del sentido de la vida y lo comparten con discípulos, lo cual conlleva serios peligros. A continuación, realizaré un análisis junguiano del fenómeno observado entre el líder espiritual Osho y sus discípulos durante las décadas de 1970 y 1980, como ejemplo representativo del tipo de riesgo que implican los procesos grupales en la búsqueda del desarrollo personal, cuando líder y discípulos se identifican inconscientemente con los arquetipos colectivos del profeta y el discípulo.

El movimiento Osho

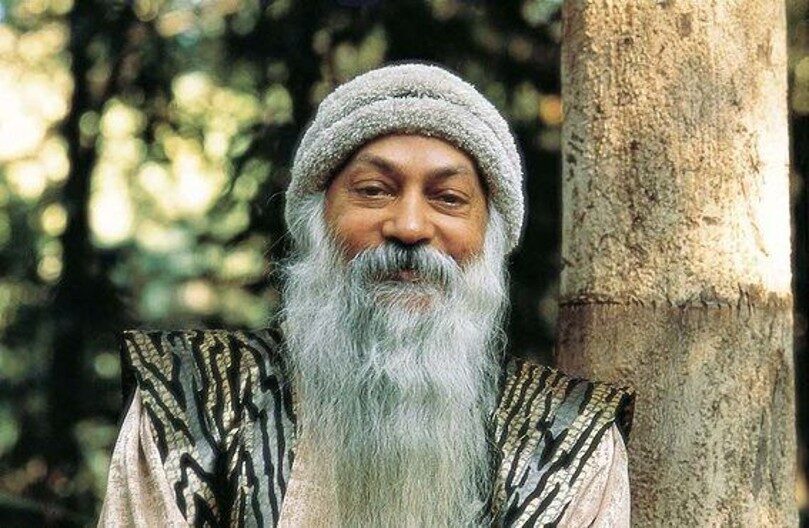

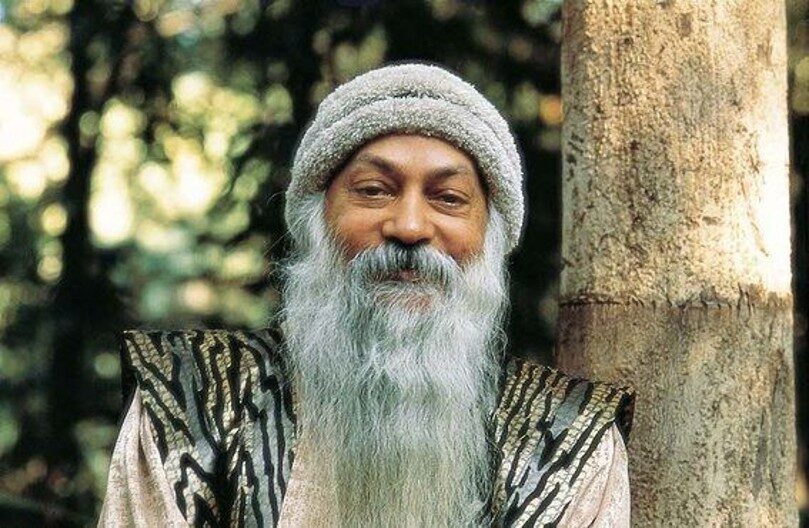

Osho nació en la India en el año 1931. Ya adulto, en el año 1970, se estableció durante un tiempo en Bombay, donde comenzó a iniciar discípulos y asumió el papel de maestro espiritual. En el año 1974, se trasladó a Pune, donde fundó un ashram que atrajo a un número creciente de visitantes occidentales. Allí desarrolló su «Movimiento del Potencial Humano», que acaparó titulares en la India y en el extranjero debido a su ambiente permisivo y al discurso provocador de su líder.

Abogó por una actitud más abierta hacia la sexualidad, postura que le valió el apodo de “gurú del sexo”.

En 2018, Netflix estrenó una exitosa serie documental titulada Wild Wild Country (Lembi et al.), que narra el nacimiento, el desarrollo y la decadencia del movimiento. Me referiré a algunos aspectos tratados en este documental, en particular a los hechos y testimonios ofrecidos por algunos de los principales discípulos de Osho.

La propuesta inicial de Osho

Osho promovía una «meditación dinámica» que incluía respiración caótica que desembocaba en hiperventilación, una explosión emocional, una fase liberadora y una fase de silencio. El grupo participaba entonces en una meditación colectiva que empleaba deliberadamente imágenes sexuales, replicando conscientemente una orgía. Osho concebía un nuevo ser humano cuya espiritualidad no rechazaba el mundo material. Proponía específicamente aceptar la riqueza de la comunidad. Esto explica, por ejemplo, que con el paso de los años llegara a poseer numerosos Rolls Royce. Sus enseñanzas estaban claramente dirigidas a intelectuales adinerados («la flor y nata de la sociedad», como la describía su secretaria privada). El ashram de Pune era un oasis de riqueza en medio de la pobreza de la India.

Volviendo al tema central, creo que en algún momento de su vida, Osho comenzó a identificarse con el arquetipo del profeta. En Puna, empezó a hablar de ser la reencarnación de una deidad y de tener una misión mesiánica, al proponer transformar la conciencia del planeta. Buscaba crear un nuevo ser humano que no perteneciera a ningún país ni religión, sino un ser despierto que coexistiera en armonía con el resto del mundo. Consideraba que su propuesta era un experimento sin precedentes en la historia, y que sería la cuna de una nueva raza cósmica, después de que el resto del mundo fuera destruido por un gigantesco holocausto nuclear.

Riesgos del desarrollo de la personalidad

Jung se refiere al proceso de desarrollo de la personalidad como el proceso de individuación, mediante el cual todos los seres humanos buscan llegar a ser ellos mismos. Esto implica una doble tarea. Internamente, debemos conocer e integrar nuestros aspectos oscuros. Externamente, debemos buscar diferenciarnos psicológicamente de las figuras colectivas, diferenciándonos de los demás seres humanos, sin aislarnos, sino manteniendo una relación con ellos. Deseo centrarme en esta segunda tarea de la individuación, ya que existe un gran peligro de identificarnos inadvertidamente con algunos de los arquetipos del inconsciente colectivo. En nuestro caso, el riesgo reside en identificarnos con los arquetipos del profeta o del discípulo. Este es un peligro inherente a cualquier proceso de autoexploración, ya sea que se lleve a cabo mediante un proceso de psicoanálisis o a través de un movimiento como el de Osho.

Partamos de la base de que, en cada una de estas vías de desarrollo psíquico, se requiere el contacto con el inconsciente, lo cual conlleva riesgos importantes. Un avance saludable en la individuación implica la transferencia de contenidos del inconsciente personal a la consciencia, lo que provoca que algunas personas se sientan un poco más sabias. Esta actitud despierta en otras el deseo de seguirlas. Este vínculo puede ser negativo si existen circunstancias psicosociales desfavorables en el entorno y se ve reforzado si se produce en personalidades vulnerables.

Situaciones que facilitan la aparición de profetas

Jung afirma que los profetas suelen aparecer en tiempos difíciles, cuando la humanidad se encuentra en un estado de confusión, como cuando se ha perdido una guía ancestral y se necesita una nueva. Cuando surgió el movimiento Osho, la guerra de Vietnam comenzó en Estados Unidos y la gente dejó de creer en lo que decía el gobierno, cuestionando la validez de sus religiones y creencias. Esto generó una rebelión entre los jóvenes que buscaban respuestas en su interior.

En Así habló Zaratustra de Nietzsche (1883/2006), el profeta aparece en un momento crítico: la muerte de Dios. Esto hace necesaria la presencia de Zaratustra, pues la gente necesita reorientarse, y el anciano sabio debe aparecer para dar a luz una nueva verdad. Según el analista junguiano Anthony Stevens (1990), con el colapso del marxismo a finales de la década de 1980, el fervor revolucionario de los sectores descontentos de la sociedad tendió a canalizarse hacia la formación de sectas religiosas centradas en figuras carismáticas y autoritarias. A su vez, desde la década anterior a Osho, se habían producido casos dramáticos, como el suicidio en Guyana en 1978 de casi 1000 discípulos del movimiento Templo del Pueblo, liderado por Jim Jones.

Dinámica entre profeta y discípulo

La teoría junguiana ofrece enfoques que explican cómo los arquetipos del profeta y del discípulo pueden activarse negativamente en los individuos, atrayéndose mutuamente.

Cuando el líder que ha encontrado un sistema explicativo sobre el sentido de la vida se identifica con la figura del profeta, se produce inmediatamente una inflación psicológica y un estado de arrogancia que Jung denominó «personalidad mana» (Jung 1966). Este fenómeno de posesión se opone a la individuación y constituye el tipo de posesión que Osho pudo haber experimentado, considerando su reacción externa: un sentimiento exaltado y abrumador de sí mismo, con dones sobrenaturales, que podría ser la fuerza dentro de sí mismo que dio origen a su movimiento.

Sin embargo, este movimiento no surge únicamente de la necesidad de un individuo como Osho, que anhela alcanzar el poder. También se requiere un público que busque a alguien a quien otorgarle dicho poder. Es un fenómeno colectivo, pues las sociedades necesitan figuras mágicas. Jung afirma que, en el fenómeno de los profetas, deben confluir tanto la voluntad de poder de un individuo como la voluntad de sumisión de muchos. A nivel psicológico, se puede hablar de la posesión de este par de figuras colectivas, en este caso el profeta y el discípulo. Es como si la personalidad se disolviera en sus pares de opuestos, y la consecuencia sería que cada individuo mostraría conscientemente una de las polaridades, mientras que su inconsciente buscaría el equilibrio de esa unilateralidad con la polaridad opuesta, gracias al principio compensatorio de la psique entre lo consciente y lo inconsciente. Esta imagen puede ayudarnos: si el yo fuera la luna con sus dos caras, la cara iluminada sería la polaridad consciente, mientras que la cara oscura sería la inconsciente.

En el caso del profeta, su actitud visible será la del hombre sabio pero compensatorio: los contenidos reprimidos por la consciencia se transfieren al inconsciente, formando allí la polaridad inversa del discípulo. ¿Cómo se manifiesta esto? Bajo el sentimiento de grandeza individual que posee la figura colectiva del profeta yace una profunda inseguridad, y su arrogancia constituye la contraparte consciente y compensatoria de esa impotencia. Es precisamente su inseguridad inconsciente la que lo impulsa a buscar prosélitos para que le aseguren la fiabilidad de sus convicciones.

En los adeptos que rodean a este individuo ocurre lo contrario. La polaridad que se hace consciente en ellos es la del discípulo. De forma compensatoria, el lado reprimido forma en el inconsciente la polaridad inversa del profeta, en un intento por corregir el desequilibrio. En otras palabras, tras la inseguridad consciente de estos discípulos subyace el arquetipo del profeta, que, al no ser reconocido internamente, se proyecta externamente sobre quien parece poseer la verdad.

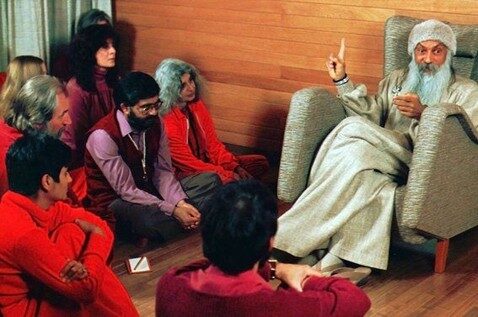

Convertir a las personas en discípulos es una situación con muchas ventajas. Jung dice: «El discípulo es indigno; con modestia se sienta a los pies del maestro y se abstiene de tener ideas propias, lo que le ahorra la molestia de pensar por sí mismo» (Jung 1966, § 263), refiriéndose a una pereza intelectual. Los discípulos de Osho no tienen grandes responsabilidades, ya que sus obligaciones recaen sobre su maestro. Tampoco necesitan descubrir las grandes verdades de la vida, pues las reciben cómodamente de él. Es decir, disfrutan pasivamente del gran tesoro de sabiduría que el gurú les transmite, iluminando al mundo, mientras que sus seguidores simplemente se dejan iluminar. Es un rol social fácil de desempeñar, ya que la responsabilidad de la iluminación se transfiere al rol del profeta, lo cual, como veremos, es una delegación peligrosa.

Existe un rasgo común entre profetas y discípulos: la aparente falta de claridad en sus límites respecto a la arrogancia y la inferioridad. Podría decirse que, psicológicamente, unos poseen una inflación psíquica, mientras que otros presentan una debilidad psíquica. Sin embargo, cabe destacar que el riesgo de esta «disolución de la persona en la psique colectiva» (ibid., § 260) es considerable, no solo para los fieles, sino también para el profeta. Ambos son víctimas del inconsciente colectivo.

Perfiles de personalidad de profetas y discípulos

Por supuesto, no todos los que se identifican con el arquetipo del profeta adoptan la dinámica del líder. Osho era una persona carismática que llenaba estadios, con una «apariencia sabia», según la definió uno de sus seguidores. Otro de ellos mencionó que quien escuchaba sus enseñanzas quedaba «como drogado», porque «canalizaba una energía que te penetraba» (Lembi et al., 2018).

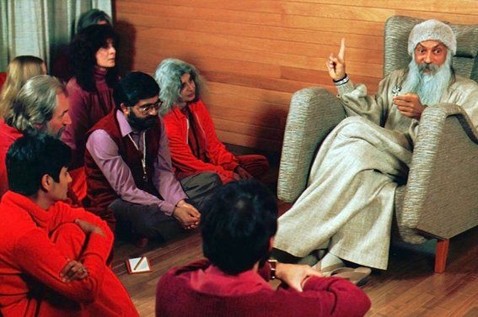

Además, la figura del profeta exige una apariencia que atraiga prestigio personal y reconocimiento general, de modo que, con el tiempo, el individuo pueda destacar por la peculiaridad de sus ornamentos y su forma de vida; es decir, por las peculiaridades de su imagen colectiva, que le permiten diferenciarse del resto. Esto sucedió con Osho, con sus numerosos Rolls Royce y sus atuendos que incluían sombreros, túnicas que resaltaban sus anchos hombros, maquillaje para mejorar su tez y una larga barba.

La práctica de rituales secretos que acentúan la preponderancia de la máscara colectiva del profeta y su prestigio mágico es constante, facilitando un éxtasis colectivo que busca disolver el yo individual de los discípulos. Algunas estrategias para lograrlo consistían en que los devotos se vistieran con túnicas naranjas, adoptaran nuevos nombres y se aseguraran de que nunca se usara el pronombre «yo», sino siempre «nosotros». Además, el líder recomendaba a sus discípulos renunciar a sus vínculos con hijos y padres, así como practicar el aborto y la esterilización, ya que los hijos se consideraban una distracción del compromiso. Todo esto fortalecía el valor de lo colectivo a expensas del yo racional.

Por el contrario, ¿qué perfil emocional suelen tener los discípulos de los profetas? En general, atraviesan situaciones de duelo personal, crisis emocionales o rupturas sociales, como la muerte de un familiar, divorcios, conflictos de pareja o desempleo, a veces agravadas por la falta de apoyo en sus redes sociales. También pueden presentarse situaciones de depresión o el inicio de etapas conflictivas, como la adolescencia o la crisis de la mitad de la vida.

En el documental de Netflix vemos cómo una mujer australiana, ferviente seguidora de Osho, relata la difícil situación en la que se encontraba resentida, enfadada y con serios problemas de pareja. Otro discípulo entrevistado, un abogado estadounidense, cuenta que, tras estudiar derecho y llevar casos exitosos como abogado litigante, se acababa de divorciar y estaba agotado y destrozado, trabajando, comiendo y bebiendo en exceso.

En la mayoría de los casos, los adeptos también tienden a mostrar una dependencia ingenua y afectiva hacia las figuras de autoridad, como se observa en los casos mencionados, donde es notoria la gran veneración y adoración que profesan a su maestro. La discípula australiana cuenta que, cada vez que se encontraba con Osho, él le daba la impresión de que «no tocaba el suelo al caminar».

El movimiento Osho en los Estados Unidos

El sueño de Osho era crear una «tierra prometida» que sirviera de modelo para el mundo. No fue posible hacerlo en Puna; era necesario albergar inicialmente a unas 2000 personas. La nueva comuna se construyó en Estados Unidos, junto a un pueblo abandonado llamado Antelope, habitado por un máximo de 50 habitantes, en su mayoría ancianos. La llegada de la enorme comunidad fue, para estos colonos, una invasión que alteró para siempre su tranquilidad. Sorprendidos, comenzaron a ver que los discípulos no solo se quedaban dentro de la ciudadela, sino que también compraban casas y negocios en el pueblo.

Pronto se desataron actos de violencia por ambas partes. Desconocidos colocaron bombas en el hotel que el grupo Osho había construido en Portland. La respuesta del movimiento fue comprar armas de fuego y comenzar un entrenamiento con armamento pesado. Posteriormente, miembros de Osho se postularon para cargos públicos y obtuvieron puestos clave, incluyendo la alcaldía. Esto les dio el derecho a cambiar el nombre del pueblo por uno oriental y a tener su propia comisaría, con agentes armados. El conflicto entre el pueblo y la comuna siguió escalando, y tiempo después, fueron miembros del movimiento Osho quienes intentaron envenenar a los aldeanos con bacterias de salmonela, depositadas secretamente en las barras de comida de varios restaurantes.

A principios de los años 80, las cosas empezaron a torcerse para el movimiento. El gobierno de Estados Unidos comenzó a investigar sucesos extraños que ocurrían en el lugar. Durante un tiempo, Osho guardó silencio voluntariamente y nombró a Sheela, una joven secretaria privada, como su portavoz, lo que le otorgó a ella un poder enorme. Más tarde se descubrió que la mayoría de los delitos investigados por las autoridades habían sido coordinados por ella. El más grave ocurrió cuando Sheela fue informada de que el gobierno estadounidense había nombrado a un fiscal para investigar el movimiento. Reunió a los miembros de su círculo íntimo para comunicarles que era necesario eliminarlo.

El fiscal y el discípulo australiano se ofrecieron como voluntarios para hacerlo. Afortunadamente, no tuvieron éxito en el ataque.

Ética individual versus ética colectiva

Esta grave situación se relaciona con otro fenómeno psicológico estudiado por Jung: el conflicto entre la ética individual y la ética grupal. Jung se oponía al concepto de pertenencia a grandes grupos, pues estaba convencido de que esto conllevaba una disminución de la responsabilidad ética personal, dado que el sujeto tendía a percibir que sus obligaciones y deberes quedaban subsumidos por la ética colectiva del grupo. Afirmó: «Cuanto más fuertes son las normas colectivas que rigen la vida de las personas, mayor es su inmoralidad a nivel individual» (Jung 1971, § 747).

Lo anterior se corrobora con la declaración de la voluntaria del ataque, quien posteriormente afirmó no poder explicar por qué se había ofrecido a cometerlo. Es como si pertenecer a la comunidad la hubiera llevado inconscientemente a actuar de forma distinta a como lo habría hecho fuera del grupo. Jung escribe: «Cuanto más se juntan los individuos, más se extinguen los factores individuales y, con ellos, la moralidad» (ibid., § 747).

Declive del movimiento

En 1985, la comuna se derrumbó cuando Osho denunció a sus colaboradores. Sheela huyó de Estados Unidos a Alemania con un grupo de veinte discípulos. Osho rompió su silencio y habló con los medios, condenando públicamente a Sheela por planear diversos delitos, entre ellos, los ataques contra el fiscal y su médico personal, el envenenamiento de los habitantes del pueblo, el robo de dinero y la piratería informática de micrófonos y teléfonos en la misma comunidad. Sheela, a su vez, respondió amenazando veladamente con revelar todos los secretos que conocía sobre el movimiento.

Las declaraciones de Osho legitimaron la entrada del FBI para investigar los crímenes. Cuando el líder vio que la investigación se dirigía contra él, intentó huir del país, pero fue capturado en el camino. El gobierno detuvo a Sheela y a Osho simultáneamente. Él fue acusado de violar las leyes de inmigración y posteriormente deportado de Estados Unidos. Veintiún países le negaron la entrada, por lo que viajó por el mundo antes de regresar a la India, donde murió en 1990. Sheela fue sentenciada a cuatro años de prisión, y su discípulo australiano, a 10 años. A pesar de todo lo sucedido, las enseñanzas de Osho han tenido un impacto notable en el pensamiento de la Nueva Era, y su popularidad ha aumentado considerablemente desde su muerte.

Conclusión

Este análisis no pretende criticar las enseñanzas de Osho ni de ningún otro líder espiritual. Es comprensible que quien ha adquirido conocimiento sobre el sentido de la vida, que le ha sido útil, sienta el deseo de compartirlo, considerando que puede ser útil para los demás. El análisis tampoco busca descartar la búsqueda de la verdad interior, que puede conducir a una sabiduría adquirida durante este proceso de autoconocimiento. La activación del arquetipo del profeta tampoco se considera un problema, ya que la individuación puede avanzar al relacionarse con esa figura interior, que puede tener cosas cruciales que comunicar. El propio Jung experimentó la presencia de este arquetipo mediante la técnica de la imaginación activa, en sus diálogos con el profeta Isaías, como relata en El Libro Rojo (2009). Lo importante es tener presente que la energía intensificada del arquetipo es una fuerza distinta a la propia.

El objetivo es evitar ser absorbido por las figuras colectivas del profeta y el discípulo, lo que puede derivar en maltratos como los ocurridos en el movimiento liderado por Osho. A menudo, las personas buscan vincularse a este tipo de grupos carismáticos, ya que la participación les brinda un sentido de pertenencia, vitalidad y compromiso, pero todo ello a costa de la desintegración de la propia identidad.

En las décadas posteriores a la muerte de Osho y hasta la actualidad, han surgido diversas sectas que se caracterizan por constituir alternativas a la sociedad establecida y promover un fuerte proselitismo, denunciando la falsedad de las religiones existentes y fomentando un cambio radical. No se trata solo de movimientos religiosos, ya que también existen sectas en ámbitos como la autoayuda o la psicoterapia, que pueden tener un carácter político o comercial.

Los grupos más peligrosos son aquellos clasificados como «sectas destructivas», que causan daños económicos a sus seguidores y, en muchos casos, violencia física, con desenlaces trágicos. Por mencionar solo algunos ejemplos, 87 miembros del movimiento de los Davidianos, con sede en Waco y liderado por David Koresh, fueron asesinados en 1993. El período comprendido entre 1994 y 1997 también estuvo marcado por el suicidio colectivo en Francia, Suiza y Canadá de 74 personas pertenecientes al movimiento Orden del Templo Solar, fundado por Joseph Di Mambro y Luc Jouret. En 1995, el ataque perpetrado por el movimiento Aum Shinrikyo, con sede en Japón y compuesto por seguidores de Shoko Asahara, cobró 12 vidas en un ataque con gas sarín. El año 1997 estuvo marcado por el suicidio colectivo de 39 personas, miembros de la secta Puerta del Cielo, liderada por Marshall Applewhite en San Diego, California.

En cada uno de estos casos, podemos encontrar individuos que se identifican con el arquetipo del profeta, invadidos por sentimientos de superioridad, teñidos de semejanza divina y acompañados de discípulos que los siguen ciegamente y aceptan ultrajes de todo tipo.

Finalmente, vuelvo a uno de los mandamientos dados por el propio Osho, pero que lamentablemente no facilitó. Dice que «La verdad está dentro de ti, no la busques en otro lugar» (Lewis & Petersen 2005, p. 186).

Referencias

Jung, CG (1966). Dos ensayos sobre psicología analítica. OC 7.

——— (1971). Tipos psicológicos. OC 6.

——— (2009). El Libro Rojo. Liber Novus, ed. S. Shamdasani. Nueva York y Londres: W.W. Norton.

Lembi, J., Way, C., Way, M., (Productores) y Way, C. y Way, M. (Directores). (2018). Wild Wild Country [Miniserie de TV; documental/crimen]. EE. UU.: Netflix.

Lewis, J. y Petersen, J.A. (2005). Nuevas religiones controvertidas. Nueva York y Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1883/2006). Así habló Zaratustra. Un libro para todos y para nadie, ed. Robert Pippin, trad. Adrian del Caro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stevens, A. (1990). Sobre Jung . Nueva York: Routledge.

____________________________________________________________________________________

ARTICLE IN ENGLISH

On prophets and disciples: the case of Osho

Juan Carlos Alonso, Bogotá, Colombia

Abstract: In times of crisis, prophets tend to emerge in different realms including that of religion. This paper undertakes a Jungian analysis of the phenomenon presented between spiritual leader Osho and his disciples in the 1970s and 1980s, as an example of the risks entailed in the type of group process where leader and followers inadvertently identify with the collective archetypes of prophet and follower. Psychosocial situations that predispose the appearance of prophets are analysed, and cases of collective suicides in recent decades are recalled. The paper also highlights the intervention of another psychological phenomenon: the conflict between the ethics of individuals versus that of groups, since large groups produce a decrease in responsibility and individual ethics.

Keywords: archetype of follower, archetype of prophet, collective ethics, individual ethics, Jung, Osho, religious cults

__________________________________________________________________

In times of social crisis, there is a tendency for the emergence of charismatic prophets and new cults, which is a phenomenon that occurs in different areas, not merely at the religious level. It begins with individuals who find their own ‘explanatory system’ of the meaning of life and who share it with disciples, which carries with it serious dangers. I will now carry out a Jungian analysis of the phenomenon presented between the spiritual leader Osho and his disciples during the 1970s and 1980s as a representative example of the type of risk involving group processes in search of personal development, when leader and disciples unconsciously identify with the collective archetypes of the prophet and the disciple.

The Osho movement

Osho was born in India in 1931. As an adult, in 1970, he settled for a time in Bombay, where he began initiating disciples and took on the role of a spiritual teacher. In 1974, he moved to Puna, where he established an ashram that attracted a growing number of Western visitors. There, he developed his ‘Human Potential Movement’, which made headlines in India and overseas due to its permissive climate and provocative talk from its leader. He advocated for a more open attitude towards sexuality, a position that earned him the nickname ‘sex guru’.

In 2018, Netftix released a successful documentary series called Wild Wild Country (Lembi et al.), which chronicles the birth, development and decline of the movement. I am going to refer to some aspects related in this documentary, particularly the facts and testimonies offered by some of Osho’s main disciples.

Osho’s initial proposal

Osho promoted a ‘dynamic meditation’, which included chaotic breathing leading to hyperventilation, an emotional explosion, a liberating phase, and a silence phase. The group then joined in a collective meditation that deliberately employed sexual imagery, consciously replicating a sexual orgy. Osho conceived of a new human being whose spirituality did not reject the material world. He specifically proposed accepting the wealth of the community. That explains, for example, the fact that over the years, Osho came to own numerous Rolls Royce cars. His teachings clearly aimed at wealthy intellectuals (‘the cream of society’, as his private secretary would describe it). The ashram in Puna was an oasis of wealth amidst the poverty of India.

Returning to the central theme, I believe that at some point in his life, Osho began to identify with the archetype of the prophet. In Puna, he began to speak of being the reincarnation of a deity and of having a messianic mission, as he proposed to transform the planet’s consciousness. He sought to create a new man who did not belong to any country or religion, but who was rather an awakened being that coexisted in harmony with the rest of the world. He considered that what he proposed was an experiment that had never been proposed before in history, and that it would be the cradle of a new cosmic race, after the rest of the world had been destroyed by a gigantic nuclear holocaust.

Risks of personality development

Jung refers to the process of personality development as the process of individuation, through which all human beings seek to become themselves. This involves a double job. Internally, we must know and integrate our dark aspects. Also externally, we must seek to differentiate ourselves psychologically from collective figures, becoming different from other human beings, without isolating ourselves, but rather maintaining a relationship with them. I wish to focus on this second task of individuation, as there is great danger of inadvertently identifying ourselves with some of the archetypes of the collective unconscious. For our case, the risk consists of identifying ourselves with the archetypes of the prophet or the disciple. This is an inherent danger in any process of self-exploration, whether it is carried out through a process of psychoanalysis or through a movement such as Osho’s.

Let us start from the fact that in each of these paths of psychic development, we are required to contact the unconscious, which presents major risks. A healthy advance in individuation leads to transferring contents from the personal unconscious to consciousness, causing certain people to feel a little wiser. This attitude awakens in other individuals the desire to follow them. This link can be negative if there are unfavorable psychosocial circumstances in the environment and is further strengthened if it occurs in vulnerable personalities.

Situations that facilitate the appearance of prophets

Jung states that prophets often appear in times of trouble, in times when humanity is in a state of confusion, such as when an ancient guidance has been lost and a new one is required. When the Osho movement emerged, the Vietnam War began in the United States and people were ceasing to believe in what the government said, questioning the validity of their religions and beliefs. This generated a rebellion among young people who were in search of answers within themselves.

In Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883/2006), the prophet appears at a time when something serious has happened: God has died. This makes the presence of Zarathustra necessary, as people need a reorientation, and the old sage must appear to give birth to a new truth. According to Jungian analyst Anthony Stevens (1990), with the collapse of Marxism in the late 1980s, revolutionary fervour amongst disgruntled members of society tended to be channeled into the formation of religious cults centred on ruthlessly authoritarian and charismatic figures. In turn, since the decade before Osho, there had been dramatic cases, such as the suicide in Guyana in 1978 of almost 1,000 disciples of the Peoples Temple movement, led by Jim Jones.

Dynamics between prophet and disciple

Jungian theory offers approaches that explain how the archetypes of the prophet and the disciple can be negatively activated in individuals, attracting each other.

When the leader who has found an explanatory system about the meaning of life identifies with the prophet’s figure, a psychological inflation and a state of arrogance that Jung referred to as the ‘mana personality’ (Jung 1966) immediately occurs. This phenomenon of possession is opposed to individuation and comprises the type of possession that Osho may have experienced, considering his external reaction: an exalted and overflowing feeling of himself, with supernatural gifts, which could be the force within himself that gave birth to his movement.

Nevertheless, such a movement does not arise only from the need of an individual such as Osho, who wishes to achieve power. There also needs to be an audience in search of someone to whom they can grant such power. It is a collective phenomenon, as societies need magical figures. Jung states that, in the phenomenon of the prophets, both the will to power of one individual and the will of submission of many must be gathered. At the psychological level, one can discuss a possession of this pair of collective figures, in this case being the prophet and the disciple. It is as though a dissolution of the personality takes place in its pairs of opposites, and the consequence will be that each individual will consciously show one of the polarities, while their unconscious will seek the balance of that one-sidedness with the opposite polarity, thanks to the compensatory principle of the psyche between the conscious and the unconscious. This image can help us: if the self were the moon with its two sides, the light side would be the conscious polarity, while the dark side would be the unconscious one.

In the case of the prophet, his visible attitude will be that of the wise yet compensatory man – the contents repressed by the consciousness are transferred to the unconscious, forming there the reverse polarity of the disciple. How does this manifest? Underneath the grandiose feeling of the individual possessed by the collective figure of the prophet lies a very deep insecurity, and his arrogance comprises the conscious and compensatory counterpart of that helplessness. It is precisely his unconscious insecurity that then drives him to seek out proselytes in order for them to assure him that his convictions are reliable.

The opposite happens in the adepts that surround this individual. The polarity that becomes conscious in them is that of the disciple. In a compensatory manner, the repressed side forms in one’s unconscious the inverse polarity of the prophet, in an attempt to correct the imbalance. In other words, behind the conscious insecurity of these disciples is the archetype of the prophet, who, not being recognized internally, is projected externally on to whoever appears to be the possessor of the truth.

Turning people into disciples is a situation that has many advantages. Jung says, ‘the disciple is unworthy; modestly he sits at the master’s feet and guards against having ideas of his own, and that saves him the trouble of thinking for himself’ (Jung 1966, § 263), as he speaks of an intellectual laziness. Osho’s disciples do not have great responsibilities, as their obligations are unloaded onto their master. Nor do they need to discover the great truths of life, as they receive them comfortably from him. That is, they passively enjoy the great treasure of wisdom that the guru transmits to them, enlightening the world, while his followers simply allow themselves to be enlightened. It is an easy social role to fulfill since the responsibility of enlightenment is transferred to the role of the prophet, which, as we will see, is a dangerous delegation.

There is something in common among prophets and disciples, and that is the fact that both appear to have unclear limits regarding arrogance and inferiority. One could say that, psychologically, one has a psychic inflation, while the others have a psychic deflation. Nevertheless, something that must be stressed is the fact that the risk of this ‘dissolution of the persona in the collective psyche’ (ibid., § 260) is great, not only for the faithful, but also for the prophet. Both are victims of the collective unconscious.

Prophet and disciple personality profiles

Of course, not everyone that identifies with the archetype of the prophet takes on the leader’s dynamics. Osho was a charismatic person who filled stadiums, with a ‘wise appearance’, as defined by one of his followers. Another of his followers mentioned that whoever listened to his teachings was ‘as if they were drugged’, because ‘he channeled an energy that got inside you’ (Lembi et al., 2018).

Additionally, the figure of the prophet also requires an appearance that attracts personal prestige and general recognition, so that over time, the individual can stand out for the peculiarity of his ornaments and ways of life – that is to say, the peculiarities of one’s collective mask, which allow one to stand out from the rest. That happened to Osho with his many Rolls Royce cars and his outfits featuring hats, tunics that highlighted his broad shoulders, make-up to improve his complexion, and a long beard.

The possession of secret rituals that accentuate the preponderance of the prophet’s collective mask and magical prestige is also constant, facilitating a collective ecstasy that seeks to dissolve the individual self of the disciples. Some of the strategies to achieve this consisted in having devotees dress in orange robes and take on new names and ensuring that the pronoun ‘I’ was never used, but rather always ‘we’. Moreover, the leader recommended that his disciples renounce their ties with children and parents, as well as engaging in the practice of abortions and sterilization, as children were considered a distraction from commitment. All of this strengthened the value of the collective at the expense of the rational self.

Conversely, what emotional profile do the disciples of the prophets usually have? In general, they are usually going through personal grief situations, emotional crises, or social ruptures, such as the death of a family member, divorces, couple conflicts or unemployment, sometimes aggravated by failures in the social networks of support of these people. There can also be situations of depression, or the beginning of conflictive ages, such as adolescence or the mid-life crisis.

In the Netflix documentary we see how an Australian woman, a fervent follower of Osho, recounts the critical situation in which she found herself resentful, angry and with serious relationship problems. Another disciple interviewed, an American lawyer, says that after studying law and handling successful cases as a trial lawyer, he had just gotten divorced and was tired and destroyed, working, eating and drinking too much.

In most cases, there is also a disposition among the adepts to show a naïve and affective dependence on people with authority, which is noted in the cases mentioned, in which a great tendency to veneration and adoration towards their teacher is notorious. Whenever the Australian disciple met Osho, she says that he gave her ‘the impression that he was not touching the ground when he walked’.

The Osho movement in the United States

Osho’s dream was to create a ‘promised land’ that would be a role model to the world. It was not possible to do it in Puna; it was necessary to house initially around 2,000 people. The new commune was built in the United States next to a lost town called Antelope, inhabited by a maximum of 50 inhabitants, mostly older people. The arrival of the huge community was, among these settlers, an invasion that forever changed their tranquility. Shocked, they began to see that the disciples were not just staying inside the citadel, but also buying houses and businesses in the town.

Acts of violence on both sides soon took place. Unknown individuals planted bombs in the hotel the Osho group had built in the city of Portland. The movement’s response was to buy firearms and begin heavy-weapon training. Subsequently, Osho members ran for public office and took over top positions, including the mayor’s office. That gave them the right to change the town’s name to an oriental name and to have their own police station, with officers carrying weapons. The conflict between the town and the commune continued to escalate, and sometime later, it was members of the Osho movement who sought to poison the villagers with Salmonella bacteria, secretly deposited in the food bars of various restaurants.

In the early 1980s, things began to take a wrong turn for the movement. The United States government began to investigate strange things that were happening at the site. For some time, Osho had entered into a voluntary silence, appointing Sheela, a young private secretary, as his spokesperson, which gave her enormous power. It was later discovered that most of the crimes being investigated by the authorities had been coordinated by her. The most serious happened when Sheela was informed that the U.S. government had appointed a prosecutor to investigate the movement. She gathered her closed group members to inform them that it was necessary to eliminate that prosecutor, and the Australian disciple volunteered to do so. Fortunately, they had no luck in the attack.

Individual ethics versus collective ethics

This serious situation is related to another psychological phenomenon studied by Jung, which is the conflict between individual ethics and group ethics. Jung was opposed to the concept of belonging to large groups, as he had the conviction that these produced a decrease in personal ethical responsibility, given that the subject tended to see that their obligations and duties were absorbed by the collective group ethics. He said: ‘The stronger the collective norms that govern people’s lives, the greater their immorality at the individual level’ (Jung 1971, § 747).

The above is verified by a statement given by the volunteer of the attack, who later declared that she could not explain why she had offered to commit the attack. It is as if belonging to the community had led her to unconsciously act differently than she would have acted outside the group. Jung writes: ‘The more individuals come together, the more individual factors become extinct, and with them, morality’ (ibid., § 747).

Decline of the movement

In 1985, the commune collapsed when Osho denounced his collaborators. Sheela fled the United States to Germany, with a group of 20 of her disciples. Osho abdicated his silence and spoke to the media, publicly condemning Sheela for the planning of various crimes, including among others, the attacks on the prosecutor and his personal doctor, poisoning of the townspeople, money theft, and microphone and telephone hacking in the same community. Sheela in turn replied by subtly threatening to reveal all the secrets she knew about the movement.

Osho’s statements legitimized the entrance of the FBI to investigate the crimes. When the leader saw that the investigation was directed against him, he tried to flee the country but was captured on the way. The government apprehended Sheela and Osho simultaneously. He was charged with violations of immigration laws and was subsequently deported from the United States. Twenty-one countries denied his entry, so he travelled the world before returning to India, where he died in 1990. Sheela was sentenced to four years in prison, and her Australian disciple, to 10 years. Despite all that has happened, Osho’s teachings have had a remarkable impact on New Age thinking, and their popularity has increased considerably since his death.

Conclusion

This analysis is not a criticism of the teachings of Osho or any of the many other spiritual leaders. It is very understandable that someone who has acquired knowledge about the meaning of life, which has served him, feels the desire to share it, considering that it can be useful to others. The analysis does not propose either to dismiss the search for inner truth, which can lead to a ‘wisdom’ acquired during this process of self-knowledge. The fact that the archetype of the prophet is activated is not considered a problem either, as individuation can advance by relating to that inner figure, who may have crucial things to communicate. Jung himself experienced the presence of this archetype through the technique of active imagination, in his dialogues with the prophet Isaiah, as he reports in The Red Book (2009). The important thing is to keep in mind that the inflated energy of the archetype is a different force from oneself.

The aim is to avoid being possessed by the collective figures of the prophet and the disciple, which can result in mistreatment such as that which occurred in the movement led by Osho. Individuals often like to link to this type of charismatic group, as participation in it gives them a sense of belonging and a sense of vitality and commitment, but everything is done at the cost of the disintegration of one’s personal identity.

In the decades following Osho’s death and up to the present day, a number of sects have emerged, characterized by constituting alternatives to the established society and promoting strong proselytism, which state the falsehood of existing religions and promote radical change. These are not only religious movements, as it is possible to find sects in fields such as self-help or psychotherapy, which can also have a political or commercial nature.

The most dangerous of these groups are those classified as ‘destructive sects’, which result in economic damage to their followers and, in many cases, physical violence, ending in tragedies. To mention just a few of them, 87 members of the Waco-based Branch Davidians movement, led by David Koresh, were killed in 1993. The period 1994-1997 was also marked by the collective suicide in France, Switzerland and Canada of 74 people belonging to the Order of the Solar Temple movement, founded by Joseph Di Mambro and Luc Jouret. In 1995, the attack carried out by the Japan-based Aum Shinrikyo movement, composed of followers of Shoko Asahara, claimed 12 lives in a sarin gas attack. The year 1997 was marked by the collective suicide of 39 people, members of the Heaven’s Gate sect, led by Marshall Applewhite in San Diego, California.

In each of these cases, we can find individuals who identify with the archetype of the prophet, invaded by feelings of superiority, tinged with divine resemblance, and accompanied by disciples blindly following them and accepting outrages of all kinds.

Finally, I return to one of the commandments given by Osho himself, but which unfortunately he did not facilitate. It states that ‘Truth is within you, do not search for it elsewhere’ (Lewis & Petersen 2005, p. 186).

References

Jung, C.G. (1966). Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. CW 7.

——— (1971). Psychological Types. CW 6.

——— (2009). The Red Book. Liber Novus, ed. S. Shamdasani. New York & London:

W.W. Norton.

Lembi, J., Way, C., Way, M. (Producers) Way, C. & Way, M. (Directors). (2018). Wild Wild Country [TV mini-series; documentary/crime]. USA: Netflix.

Lewis, J. & Petersen, J.A. (2005). Controversial New Religions. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1883/2006). Thus Spoke Zarathustra. A Book for All and None, ed. Robert Pippin, trans. Adrian del Caro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stevens, A. (1990). On Jung. New York: Routledge.