CREATING OUR OWN BLACK BOOKS: keeping a journal as a loom of life

Por Mónica Pinilla Pineda. Analista SCAJ.

Published in Journal of Analytical Psychology (Feb. 2022)

Para la versión en portugués, da click aquí

Abstract: Jung’s The Black Books are annotations of his inner world after his process of self-experimentation, which he called his ‘confrontation with the unconscious’. They preceded The Red Book in which, as a scribe, he reworked his initial notes and drawings. This was the raw material for the work that Jung developed over the rest of his life. From his experimentation, he formulated the method of active imagination and the concept of the transcendent function, a psychological function that creates symbols and integrates the unconscious contents in consciousness. Jung invites us, with his experience, to write and paint our own Black Books and to explore our inner images. With this proposal to keep a journal as a loom of life, we welcome his invitation, which allows us to weave and integrate the visible and invisible substances of our lives. Our intention for the journalling is to provide a space for the unfolding of the individuation process. In Jung’s invitation we see that a life that does not confront itself cannot be realized as such.

Keywords: Black Books, The Red Book, active imagination, transcendent function, inner journal as a loom of life

Symbols. All symbols…Maybe everything is a symbol…Would you be a symbol too?

(Fernando Pessoa 2012)

Introduction

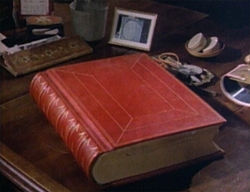

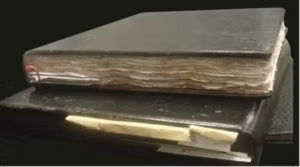

Jung’s The Black Books (2020) have been recently published. They consist of the notebooks in which Jung wrote, between 1913 and 1932, notes on his inner world. These Black Books preceded his work on his Red Book, in which he transcribed and reworked his initial notes and drawings as a scribe. After the crisis he experienced following his falling out with Freud, Jung began a process of self-experimentation, which he referred to as his ‘confrontation with the unconscious’. He was involved in meditative practices in order to delve deeper into himself to obtain material from the unconscious in the form of images and dialogues with them. The material that he first gathered in black notebooks became the basis for his later drafting of the Red Book, in which he wrote and painted his inner exploration. In his memoirs Jung comments:

All my works, everything that I have created spiritually, part of my initial imaginations and dreams. In 1912, I began what has lasted for almost fifty years. Everything that I have done in my later life is already contained in them, albeit only in the form of emotions or images.

(Jung 2002, p. 229)

Beginning with his confrontation with the unconscious, Jung went on to formulate and describe his method of active imagination in his 1916 text, The Transcendent Function. Here, he develops the method for establishing contact with the contents of the unconscious via activation of the transcendent function – a psychological function that creates symbols while integrating the unconscious contents into consciousness. I initially titled this paper: ‘Making our own Red Books’, but I settled on ‘Creating our own Black Books’, both out of consideration of Jung’s own claims but also because of his proposal, namely, to invite one to keep a journal as the loom of life. It is a simple and complex invitation to know oneself by making written and painted annotations of explorations and discoveries of our internal worlds.

Active imagination and the transcendent function

With the publication of Jung’s The Black Books (2020), we are witnesses to his internal exploration and to the symbols that emerged thanks to the transforming psychological function of energy or transcendent function. It is striking that the editor of The Black Books (2020) has subtitled them Notebooks of Transformation, alluding to both their symbolic content and to their transformative potential[1]. Nevertheless, we can recognize them as journals of the inner journey that Jung undertook starting in 1913, following his falling out with Freud. In his lecture ‘Active Imagination: an Introduction’, Murray Stein (2020) comments that, in the 1980s, he had the privilege of spending some days with Michael Fordham, a close collaborator of Jung. At some point during those days, Fordham asked him:

‘You know what was Jung’s greatest discovery?’.

While Stein thought that he would tell him about the archetypes or the collective unconscious, Fordham replied:

‘Jung’s greatest discovery was the inner world’.

This discovery was the product of the journey that he undertook through active imagination and which, from then on, would be his way of discovereing and working with the contents of the unconscious. It was an inner journey, the understanding and integration of which would not only take up the rest of his life but would also be the legacy he left behind for humanity. The first sketches of his exploration were reflected in The Black Books (2020) and his first elaborations can be found in The Red Book (2010). Jung recognizes this process as fundamental:

The years when I was already trying to clarify the internal images constituted the most important part of my life in which everything essential was defined.… All my subsequent activity consisted of perfecting what sprang from the unconscious, and that began to flood me. It was the raw material for my life’s work.

(Jung 2002, p. 237)

Let us reflect on the process of active imagination that facilitates this approach to the unconscious and the spontaneous production of images. Walter Boechat (2017) synthesizes the process of active imagination in four successive actions: 1) empty; 2) let go; 3) impregnate; and 4) confront ethically. The first thing is to empty one’s mind of daily content, so that the images of the unconscious can arise spontaneously. Then, the interference of consciousness stops, and the images that emerge are followed. Thus, imagination is allowed to fly freely, letting itself be carried away by the images that are contemplated, while they continue their course. According to Jung, some people allow their hands to express these images through plastic materials, while others do so through dance and movement. In any case, Jung recommends that the experience be recorded either in writing or drawing. This allows for the full expression of both lived experience and felt emotion as an attempt is made to both tangibly and symbolically shape the content that has emerged, making it, in some way, accessible to consciousness. ‘This supposes the beginning of the transcendent function, that is, the collaboration between the unconscious and the conscious data’ (Jung 1916/1959, para. 167).

Jung refers to the importance of working with the contents of the unconscious in order to face and then integrate the compensatory material into the entirety of one’s personality thereby bringing greater consciousness which helps to promote balance. The ego, the core subject of consciousness, tends to be considered the main driver, its scope being limited and unilateral. In the prologue to The Transcendent Function, Jung states:

The method of active imagination is the main resource for the production of those contents of the unconscious that are, in a way, below the threshold of consciousness and that, once intensified, would be the first to spontaneously break into it … The meaning and value of these fantasies are not revealed until they are integrated into the entirety of the personality, that is, until one faces their true meaning and confronts them morally.

(Jung 1916/1959, p. 71)

Jung compares this psychological function that articulates the unconscious in consciousness with the mathematical function that articulates real and imaginary numbers. In his book Symbols of Transformation (1912/1952), Jung proposed the existence of two types of thought. One is a directed, rational and linear thought that adapts to external reality. This is the thought of consciousness and science. The other is fantasized thinking, which is circular and associative, and is closer to the unconscious. It is the proper language of myths, imagination, and dreams.

The integration of these two types of thinking is of vital importance. Here, we find the ability to create symbols that reveal forces and contents that guide the fundamental affairs of the human soul. This was the work that Jung undertook in his Red Book, by transcribing and attempting to understand, through explanations and poetic elaborations, the meaning of the images and emotions that flooded him, translating them into personified figures and dialogues that he held with them. In the introduction to the Red Book, Shamdasani comments:

Jung argued that the meaning of these fantasies was linked to the fact that they arose from the mythopoietic imagination, which has disappeared in the present rational age. The task of individuation lies in the establishment of a dialogue with the figures of fantasy – or contents of the collective unconscious – and in their integration into consciousness, to retrieve, thus, the value of mythopoietic imagination.

(Shamdasani 2010, p. 209)

Shamdasani comments that Jung, after his experience of confrontation with his unconscious, suggested that his patients paint and write the images that emerged from their inner processes, that is, he invited them to make their own notes as journals or transformation notebooks. In a letter to Gilbert, he remarked: ‘Sometimes, I find it helpful to handle a case to give the patient the courage to express his particular content, whether in the form of writing or by drawing and painting’ (Shamdasani 2010, p. 217). This is also recognized by Boechat, as follows: ‘With the intense experience of his own unconscious that he expressed in the Red Book, Jung invites us to write our own Red Book and confront our own images’ (Boechat 2017, p. 66).

The Black Books will create challenges for understanding Jung’s work, just as the The Red Book did in the last decade. Both books are really the intimate records of the inner journey that Jung undertook and which he called his most difficult experiment: the confrontation with that inner universe of the unconscious, which arose from the question of his inner myth and of his soul, when it was lost.

My experience with journals: notebooks of human exploration

In his introduction to The Red Book, Shamdasani says: ‘The Black Books are not journals recording events…. Rather, they are records of an experiment’ (Shamdasani 2010, p. 201). He understands ‘journals’ to be records of external occurrences and events, preferring, therefore, to call these texts ‘notebooks of transformation’. Shamdasani regards The Black Books as the record of Jung’s active imaginations and the representation of his mental states, as well as his reflections on them. Following this entry by Shamdasani, I will in turn assume and understand journals, in general terms, as notebooks of the inner world of the person who keeps them. They are notebooks that collect not only external events, but also images, dreams, and emotions. Since the inception of writing, journals have accompanied the processes of inner exploration and human creativity. We find many examples from the worlds of art, literature and philosophy –Dostoyevsky’s (2010) A Writer’s Diary (an exercise in writing that helped him to incubate his literary work), The Diary of Frida Kahlo (2008)(a container for her emotional world, as well as a place for the sketches of many of her paintings), Goethe’s many travel journals, Heidegger’s famous Black Notebooks (2017) (in which the thinker reflects on his philosophical itinerary) and Kierkegaard’s (1993) Diary. All these notebooks, some with drawings, are truly an incubation laboratory for works of art and human thought. These are notebooks that contain, like Jung’s The Black Books, the raw material of a life’s work.

We have all had some experience with journals. For example, as a child, I remember having a diary with a little key to which I made confessions. My diary was my first temenos or container, a place secured with a key where my confessions could be protected from external glances. I remember writing to myself and to another wiser one within me, during each existential crisis that I went through during my adolescence and youth, especially in those moments of encounter with love and lovelessness, that is, moments of loss. These scenarios are marked by encounters with the emotional emptiness of absence, small learnings of death. A journal would always accompany me on my journeys.

I have kept a journal with my reflections, insights and dreams for many years. My journal has also served as a needed ritual to mark the closing and opening of the years. As well as writing, I have also made use of colour and have made collages about the development of my life. Spontaneously, I tended to illustrate the writings with images that emerged in that space of my diary, a space into which I entered and to which I sought to return. My diary served as an interior space that, paradoxically, was located outside. Without a doubt, it was a transitional space between the inside and the outside. Unexpected processes of expression and elaboration were unleashed in my journal. The journal was a laboratory of interiority.

Already with the experience of my journals, in 2008 I explored Ira Progoff’s (1992) intensive journal process with my teacher Alejandro Angulo. This important meeting of ‘two masters’ helped me connect Progoff’s method with Angulo’s experience with the spiritual exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola and with the spiritual path of many mystics. This journal work was like love at first sight for me. This relationship between human interiority and writing felt as if it was a part of me.

A year later, in 2009, with some trepidation I embarked on the journey of Progoff’s five-day Intensive Journal workshop. Although this was undertaken in a language that I’m not that familiar with, I discovered a new dimension of time and my interest grew. The image that emerged at the end of the first group journal workshop was a handloom – a wooden square on which I sketched a multicoloured fabric, suspended between stars. I wrote: ‘inner journal: a multicoloured fabric that connects me and throws me into infinity’. I had recently begun my training as a Jungian analyst. That same year, The Red Book was published. Writing and painting in a journal has always been a Jungian practice for me. A few years earlier, my Master’s degree work in literature had been an archetypal analysis of an autobiographical novel by Elena Poniatowska that I called ‘Weaving a Life in Elena Poniatowska’s Fleur-de-Lis’.Already there, my interest in the autobiographical and its understanding as ‘tissue’ appeared.

Without knowing it, all these threads would lead to the proposal to accompany others to keep their journal as the loom of life.

The diary as the loom of life

The Loom of Life proposal has been configured as a method of working on oneself following an ancient path of personal exploration: keeping an intimate journal. Individual work is carried out on a journal in a group sitting in shared silence. Initially, various areas of life experience are addressed, weaving threads of historical life that develop the bases of an autobiography, not for others, but for oneself. Secondly, invisible threads of connection with the inner fabric of wisdom are encouraged in order to seek connection with the spirit of the depths in order to discover the myth that gives meaning to life itself. The loom of life is a way of referring metaphorically to the integrating function of the psyche through its ability to self-regulate and produce symbolic images, as Jung recommended. We can recall the poet Rilke: ‘Before looking outside…. Let me take a look inside myself’. By weaving life through a diary, a journey of self-exploration and inner discovery is undertaken which supports the development of the individuation process. A life that is not woven is a life that cannot be realized as such.

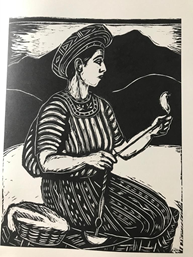

As we bring to mind the image of ancient artisan looms (see Figure 1), we find that weaving is an activity that takes place in the interweaving of threads between a vertical axis and a horizontal axis. The basic yarns are the warp. The threads that intersect are the weave with which it is woven. In this crossing of threads the textile is manufactured. On the image of the fabric, The Book of Symbols (2011) states that:

The crossing of two sets of perpendicular threads – called warp and weft – is the basic principle of weaving. With these simple techniques, fabrics of such complexity are produced that weaving has become an image of the mystery of existence. It is the crossroads of time and space, where the visible and invisible worlds are interwoven, where each created form becomes a thread in the great tapestry of life.

(Martin 2011, p. 456)

Figure 1. Guatemala´s backstrap weaver

(Anderson 2016, p. 35)

In this interweaving between warp and weft, a fabric is generated that connects earth and sky, the visible and the invisible, matter and spirit. The upper crossbar of the frame of the loom is called the sky beam, while the lower crossbar represents the earth. Between heaven and earth, the cloth is woven as a creation. Similarly, our lives are woven like threads in a loom. The interweaving of these visible and invisible threads forms the unique fabric of every human life.

In mythology, three spinning women are at the origin of every life. They are the goddesses of fate. In Roman mythology, the Fates, in Nordic mythology, the Norns, and in Greek mythology, the Moiras — Clotho, who spins the thread of life, Lachesis, who measures and distributes it and Atropos, the inexorable, who decides when to cut it. The thread represents the time that is given to us. Birth, life and death, the constituent elements of all life, are represented by these three spinning goddesses of human destiny. We can see how life is related to the metaphor of weaving. We enter the spiral of life when our existence begins to be spun with the spindle. ‘And everything begins with a single thread, as Plato tells us, wound around the spindle of the rotating cosmos that is held on the lap of a woman, who creates the fate of the world by spinning it’ (Martin 2011, p. 458). It is also spun through the journal, just as it is done with the cotton that is passed through the spindle to obtain the thread with which to weave. The loom of life expresses the work we perform to weave the visible and invisible substance of our lives in a journal. This process requires making threads, weaving threads that have been loose, discovering the warp on which our life is sustained and the visible and invisible wefts, which have given it its particular shape and colour.

Figure 2. Guatemala´s Cotton Spinner

(Anderson 2016, p. 25)

The journal is a way to weave our own life and to weave ourselves in the great loom of life. First, threads of personal life are woven, recognizing the warp that has structured us and discovering the plots of life itself. Thus, the field of personal complexes is approached, with the goal of broadening biographical consciousness. It works around the space-time dimension: where am I in my life?, where do I come from?, and where does the fabric of my life seem to lead me? This is how one develops an ‘Autobiography for Oneself’. It is a tentative development because, as long as we live, we will always have material to continue feeding the biography. Secondly, the invisible threads and the vital sense are wrought. Aspects that emerge in the process of deepening the internal world through dreams, emerging images in meditation and personification of emotions through internal dialogues, are addressed here. It is an invitation to let oneself be guided by one’s own archetypal nature and by the Self, which, as a totalizing archetype, self-regulates the psyche and transcends the ego. With the approach of the unconscious contents, we seek to connect with the spirit of depth and this brings the question of the internal myth that guides or interferes with the vital sense to the surface.

By weaving life through a journal, one seeks to undertake a journey that supports the development of the individuation process, that is, to travel a path of personal fulfilment in connection with the world. This process is about becoming oneself by developing an individual personality, finding a way of life to validate both the inner truth and the outer world. According to Jung, ‘as symbolism has shown since ancient times: individuation does not exclude the world, it includes it’ (Jung 1947/1954, para. 432). The goal of individuation is thus to achieve an individual development, which allows for the paradox of both differentiating oneself – separating oneself from the world – whilst at the same time remaining united to the world or, in our terms, connected to the loom of life. In his book The Principle of Individuation, Murray Stein (2007) raises the importance of finding a space for individuation. He wonders what would be the psychological space in which we can keep this process active. He characterizes this space as hermetic, alluding to the god Hermes, the messenger between the borders of consciousness and the unconscious. The function of active imagination is to constellate this hermetic space within the individual. Our proposal is for the journal as a transformation notebook to become an activating space for the individuation process.

By way of closing

The Loom of Life is our invitation to have a space for the individuation process. In this sense, it is an incubation laboratory – an invitation for our patients that can also be facilitated in group contexts. This method has also been implemented in groups in university contexts and, since 2017, in various regions of Colombia with judges, seeking to broaden their human development in the midst of complex dynamics of polarization and violence, as well as in the search for a transition towards peace. As Jung showed, the development of our personality is only achieved by entering the exploration of the inner world, confronting us with its content and allowing it to transform and expand consciousness. The Black Books (2020) are a door that opens in Jung’s exploration, just as happened with his challenging and, at the same time, magnificent The Red Book (2010). We thus invite you to collect your own raw material in journals which, as spaces for transformation, facilitate the integration of both conscious and unconscious aspects into our vital attitude. In this process of becoming ourselves, we undertake the task of integrating the visible and invisible threads of our life into the great loom of life.

References

Anderson, M. (2016). Guardianes de las Artes. Grabados de artistas y artesanos de Guatemala. Guatemala: Ediciones del Pensativo.

Boechat, W. (2017). The Red Book of C.G. Jung. A Journey into Unknown Depths. London: Karnac Books Ltd.

Dostoyevsky, F. (2010). Diario de un Escritor. Madrid: Editorial Páginas de Espuma.

Heidegger, M. (2017). Cuadernos Negros. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

Jung, C.G. (1912/1952). Símbolos de Transformación. OC 5. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

——— (1916/1959). ‘La función transcendente’. OC 8. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

——— (1947/1954). ‘Consideraciones teóricas acerca de la esencia de lo psíquico’. OC 8. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

——— (2002). Recuerdos, Sueños, Pensamientos, ed. A. Jaffé. Barcelona: Seix Barral.

——— (2010). El Libro Rojo, ed. S. Shamdasani. Buenos Aires: El Hilo de Ariadna Malba – Fundación Constantini.

——— (2020). The Black Books. Notebooks of Transformation, ed.S. Shamdasani, trans. M. Liebscher & J. Peck. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Khalo, F. (2008). El Diario de Frida Kahlo. Un Íntimo Autorretrato. México: La Vaca Independiente S.A. de C.V.

Kierkegaard, S. (1993). Diario Íntimo. Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, S.A.

Martin, K. (ed.). (2011). El Libro de los Símbolos. Reflexiones Sobre las Imágenes Arquetípicas. The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism. Madrid: Taschen.

Pessoa, F. (2012). ‘Psiquetipia (o psicotipia)’. In Poemas. Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada, S.A.

Progoff, I. (1992). At a Journal Workshop: Writing to Access the Power of the Unconscious. New York: Penguin Putnam.

Rilke, R.M. (2007). Nueva Antología Poética. Madrid: Editorial Espasa Calpe, S.A.

Shamdasani, S. (2010). ‘Liber Novus. El Libro Rojo de C.G. Jung’. In El Libro Rojo, (pp. 193-225). Buenos Aires: El Hilo de Ariadna Malba – Fundación Constantini.

Stein, M. (2007). El Principio de Individuación. Hacia el Desarrollo de la Consciencia Humana. Barcelona: Ediciones Luciérnaga.

——— (2020) ‘Active imagination: an introduction’. Recorded 17 July 2020. Confer: Talk on demand. Retrieved from http://www.confer.uk.com/ondemand/imagination.html

——————————————————

TRANSLATIONS OF ABSTRACT

Les Livres Noirs de Jung sont des annotations sur son monde intérieur suite à son processus d’expérimentation sur lui-même, qu’il a appelé sa « confrontation avec l’inconscient ». Ils ont précédé le Livre Rouge dans lequel, comme un scribe, il retravailla ses notes et dessins initiaux. Ce fut le matériel brut pour le travail que Jung développa jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. A partir de son expérimentation, il formula la méthode d’imagination active et le concept de fonction transcendante, une fonction psychologique qui crée des symboles et intègre les contenus inconscients dans la conscience.

Par son expérience Jung nous invite à écrire et à peindre nos propres Livres Noirs et à explorer nos images intérieures. Avec cette proposition de tenir un journal en tant que métier à tisser de la vie, nous accueillons son invitation, qui nous permet de tisser et d’intégrer les substances visibles et invisibles de nos vies. Notre intention dans cette expérience de tenir un journal est de fournir un espace pour le déploiement du processus d’individuation. Dans l’invitation de Jung nous voyons qu’une vie qui ne se confronte pas à elle-même ne peut pas se réaliser en tant que telle.

Mots-clés: Livres Noirs, Livre Rouge, imagination active, fonction transcendante, journal intérieur en tant que métier à tisser de la vie

Jungs Schwarze Bücher sind Anmerkungen zu seiner inneren Welt nach seinem Selbstversuch, den er seine ‘Konfrontation mit dem Unbewußten’ nannte. Sie gingen dem Roten Buch voraus, in dem er als Schreiber seine ersten Notizen und Zeichnungen überarbeitete. Dies war der Rohstoff für die Arbeit, die Jung im Laufe seines Lebens entwickelte. Aus seinen Experimenten formulierte er die Methode der Aktiven Imagination und das Konzept der transzendenten Funktion, einer psychologischen Funktion, die Symbole schafft und die unbewußten Inhalte ins Bewußtsein integriert.

Jung lädt uns mit seiner Erfahrung ein, unsere eigenen Schwarzen Bücher zu schreiben und zu malen und unsere inneren Bilder zu erforschen. Mit diesem Vorschlag, ein Tagebuch als Webstuhl des Lebens zu führen, begrüßen wir seine Einladung, die es uns ermöglicht, die sichtbaren und unsichtbaren Substanzen unseres Lebens zu weben und zu integrieren. Unsere Absicht für das Tagebuchführen ist es, einen Raum für die Entfaltung des Individuationsprozesses zu schaffen. In Jungs Einladung sehen wir, daß ein Leben, das sich nicht mit sich selbst konfrontiert, als solches nicht realisiert werden kann.

Schlüsselwörter: Schwarze Bücher, Rotes Buch, Aktive Imagination, transzendente Funktion, inneres Tagebuch als Webstuhl des Lebens

I Libri Neri di Jung sono annotazioni del suo mondo interiore dopo il suo processo di autosperimentazione, che ha chiamato il suo ‘confronto con l’inconscio’. Hanno preceduto il Libro Rosso in cui, come uno scriba, ha rielaborato le sue note e disegni iniziali. Questa è stata la materia prima per il lavoro che Jung ha sviluppato per il resto della sua vita. Dalla sua sperimentazione, ha formulato il metodo dell’immaginazione attiva e il concetto della funzione trascendente, una funzione psicologica che crea simboli e integra i contenuti inconsci nella coscienza.

Jung ci invita, con la sua esperienza, a scrivere e dipingere i nostri Libri Neri e ad esplorare le nostre immagini interiori. Con questa proposta di tenere un diario come un telaio della vita, accettiamo il suo invito, che ci permette di tessere e integrare le sostanze visibili e invisibili delle nostre vite. La nostra intenzione nel tenere un diario è di fornire uno spazio per lo svolgimento del processo di individuazione. Nell’invito di Jung vediamo che una vita che non si confronta con se stessa non può realizzarsi come tale.

Parole chiave: Libri Neri, Libro Rosso, immaginazione attiva, funzione trascendente, diario interiore come un telaio della vita

Черная книга Юнга представляет собой аннотацию его внутреннего мира после его экспериментов над собой, которые он назвал «конфронтацией с бессознательным». Она предшествовали Красной книге, в которой он как писец переработал свои первоначальные записи и рисунки. Это было сырьем для работы, которую Юнг развивал всю оставшуюся жизнь. На основе своих экспериментов он сформулировал метод активного воображения и концепцию трансцендентной функции, психологической функции, которая создает символы и интегрирует бессознательное содержание в сознание.

Юнг приглашает нас писать и разрисовывать наши собственные Черные книги и исследовать наши внутренние образы. Предлагая вести дневник как ткацкий станок жизни, мы принимаем его приглашение, которое позволяет нам сплетать и интегрировать видимые и невидимые вещества нашей жизни. Наше намерение вести дневник означает предоставить пространство для развертывания процесса индивидуации. В приглашении Юнга мы видим, что жизнь, которая не противостоит самой себе, не может быть реализована как таковая.

Ключевые слова: Черная книга, Красная книга, активное воображение, трансцендентная функция, дневник как ткацкий станок жизни

Los Libros Negros de Jung son anotaciones de su mundo interno tras su proceso de auto experimentación, al que denominó su “confrontación con lo inconsciente”. Estos antecedieron al Libro Rojo, en el que como un escriba reelaboraba sus notas y dibujos iniciales. Esta fue la materia prima del trabajo que Jung desarrolló por el resto de su vida. A partir de su experimentación formuló el método de la imaginación activa y el concepto de la función transcendente, función psicológica creadora de símbolos e integradora de contenidos inconscientes en la conciencia.

Jung nos invita con su experiencia a escribir nuestros propios Libros Negros y a explorar nuestras imágenes interiores. Con nuestra propuesta de llevar un diario como telar de la vida hemos acogido esta invitación, que nos permite, tejer e integrar la sustancia visible e invisible de nuestras vidas. Nuestra intención con el diario es facilitar un espacio para el desenvolvimiento del proceso de individuación. En la invitación de Jung vemos que una vida que no se confronte consigo misma, no se puede realizar como tal.

Palabras claves: Libros Negros, Libro Rojo, imaginación activa, función transcendente, diario como telar de la vida

创建我们自己的黑皮书:将日记作为生命的织布机

荣格的黑皮书是他自我实验过程后对内心世界的注解,他称之为“与无意识的对峙”。黑皮书的创作发生在红皮书之前,作为红皮书的草稿,他在红皮书中重新编写了他最初的笔记和图画。这是荣格在其余生展开的工作的原始材料。从他的实验中,他形成了积极想象的方法和超验功能的概念,超验功能是一种创造象征并将无意识内容整合到意识中的心理功能。

荣格依照他自己经验,邀请我们来书写和绘制我们自己的黑皮书,探索我们的内在意象。我们提出将日记作为生命的织布机的计划,接受了他的邀请,这使我们能够编织和整合我们生命中可见和不可见的存在。我们写日记的目的是,为自性化过程的展开提供一个空间。在荣格的邀请中,我们看到,假如一个生命不面对自己,它便无法实现自身。

关键词:黑皮书、红皮书、积极想象、超验的功能、内心日记作为生命的织布机

Os Livros Negros de Jung são anotações de seu mundo interior após seu processo de autoexperimentação, que ele chamou de seu “confronto com o inconsciente”. Eles precederam o Livro Vermelho no qual, como escriba, ele reformulou suas notas e desenhos iniciais. Esta foi a matéria-prima para o trabalho que Jung desenvolveu pelo resto de sua vida. A partir de sua experimentação, ele formulou o método da imaginação ativa e o conceito de função transcendente, uma função psicológica que cria símbolos e integra os conteúdos inconscientes na consciência.

Jung nos convida, com sua experiência, a escrever e pintar nossos próprios Livros Negros e explorar nossas imagens internas. Com esta proposta de manter um diário como um tear da vida, saudamos seu convite, que nos permite tecer e integrar as substâncias visíveis e invisíveis de nossas vidas. Nossa intenção para o diário é fornecer um espaço para o desdobramento do processo de individuação. No convite de Jung, vemos que uma vida que não se confronta não pode ser realizada como tal.

Palavras-chave: Livros Negros, Livro Vermelho, imaginação ativa, função transcendente, diário interno como um tear da vida

[1] The subtitle also implicitly alludes to Jung’s previous work Symbols of Transformation (1912/1957), which motivated his split from Freud.